DNA Structure |

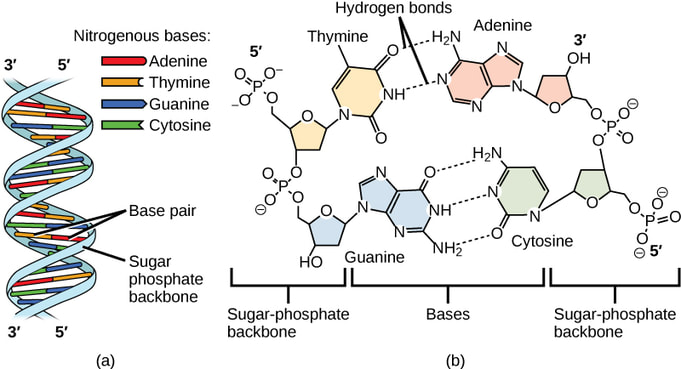

Imagine DNA as a set of instructions or a blueprint for building and maintaining living things, like plants, animals, and even us humans! The structure of DNA is like a twisted ladder, known as a "double helix." DNA is talked about as if we have known the structure for as long as we have known about atoms and molecules. But it wasn't until 1953 that the structure of DNA was discovered by two scientists, James Watson and Francis Crick.

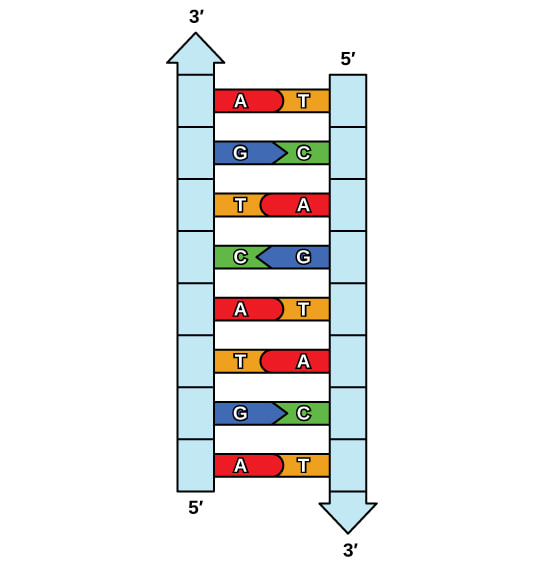

Think of DNA as a long, thin chain made up of small individual chain links called nucleotides. These nucleotides come in four different types: adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C). Nucleotides pair up with each other in a specific way: adenine always pairs with thymine, and guanine always pairs with cytosine. It's like they have a special bond with their partner. Each nucleotide partnership is called a base pair.

Now, let's talk about the twisted ladder part. Imagine that you have two chains twisted together to form a shape like a spiral staircase. That's what DNA looks like! The sides of the ladder are made of sugar and phosphate molecules, while the rungs (steps) of the ladder are the paired nucleotides we talked about earlier.

This twisted ladder shape is very important because it keeps the genetic information safe and organized. It's like a strong protective armor that prevents damage to the precious genetic code inside. Each long strand of DNA can be coiled into a single chromosome. All the chromosomes in a cell make up your individual genome. All the information that is stored in your DNA is kept safe within the nucleus of the cell.

Every living thing has its own unique DNA sequence, and this sequence of nucleotides is what makes each living thing special and different from others. The order of the nucleotides determines our traits, like eye color, hair type, and much more.

In summary, DNA is like a double helix, a twisted ladder with nucleotides as building blocks, and it holds the instructions for building and maintaining all living things. It's a fascinating and essential molecule that makes life possible!

Think of DNA as a long, thin chain made up of small individual chain links called nucleotides. These nucleotides come in four different types: adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C). Nucleotides pair up with each other in a specific way: adenine always pairs with thymine, and guanine always pairs with cytosine. It's like they have a special bond with their partner. Each nucleotide partnership is called a base pair.

Now, let's talk about the twisted ladder part. Imagine that you have two chains twisted together to form a shape like a spiral staircase. That's what DNA looks like! The sides of the ladder are made of sugar and phosphate molecules, while the rungs (steps) of the ladder are the paired nucleotides we talked about earlier.

This twisted ladder shape is very important because it keeps the genetic information safe and organized. It's like a strong protective armor that prevents damage to the precious genetic code inside. Each long strand of DNA can be coiled into a single chromosome. All the chromosomes in a cell make up your individual genome. All the information that is stored in your DNA is kept safe within the nucleus of the cell.

Every living thing has its own unique DNA sequence, and this sequence of nucleotides is what makes each living thing special and different from others. The order of the nucleotides determines our traits, like eye color, hair type, and much more.

In summary, DNA is like a double helix, a twisted ladder with nucleotides as building blocks, and it holds the instructions for building and maintaining all living things. It's a fascinating and essential molecule that makes life possible!

|

|

|

|

|

|

Honors - DNA ReplicationWhen a cell divides, it is important that each daughter cell receives an identical copy of the DNA. This is accomplished by the process of DNA replication. The replication of DNA occurs during the synthesis phase, or S phase, of the cell cycle, before the cell enters mitosis or meiosis.

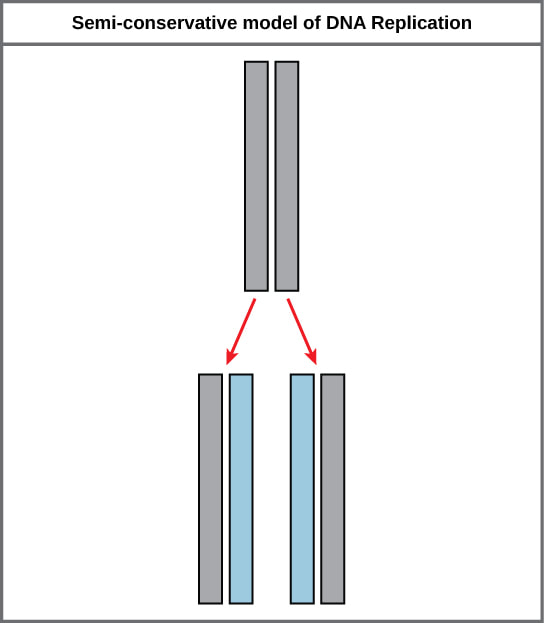

The elucidation of the structure of the double helix provided a hint as to how DNA is copied. Recall that adenine nucleotides pair with thymine nucleotides, and cytosine with guanine. This means that the two strands are complementary to each other. For example, a strand of DNA with a nucleotide sequence of AGTCATGA will have a complementary strand with the sequence TCAGTACT. Because of the complementarity of the two strands, having one strand means that it is possible to recreate the other strand. This model for replication suggests that the two strands of the double helix separate during replication, and each strand serves as a template from which the new complementary strand is copied. During DNA replication, each of the two strands that make up the double helix serves as a template from which new strands are copied. The new strand will be complementary to the parental or “old” strand. Each new double strand consists of one parental strand and one new daughter strand. This is known as semiconservative replication. When two DNA copies are formed, they have an identical sequence of nucleotide bases and are divided equally into two daughter cells.

|

DNA Replication in Eukaryotes

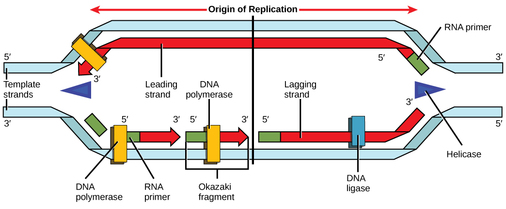

Because eukaryotic genomes are very complex, DNA replication is a very complicated process that involves several enzymes and other proteins. It occurs in three main stages: initiation, elongation, and termination.

Recall that eukaryotic DNA is bound to proteins known as histones to form structures called nucleosomes. During initiation, the DNA is made accessible to the proteins and enzymes involved in the replication process. How does the replication machinery know where on the DNA double helix to begin? It turns out that there are specific nucleotide sequences called origins of replication at which replication begins. Certain proteins bind to the origin of replication while an enzyme called helicase unwinds and opens up the DNA helix. As the DNA opens up, Y-shaped structures called replication forks are formed. Two replication forks are formed at the origin of replication, and these get extended in both directions as replication proceeds. There are multiple origins of replication on the eukaryotic chromosome, such that replication can occur simultaneously from several places in the genome.

Because eukaryotic genomes are very complex, DNA replication is a very complicated process that involves several enzymes and other proteins. It occurs in three main stages: initiation, elongation, and termination.

Recall that eukaryotic DNA is bound to proteins known as histones to form structures called nucleosomes. During initiation, the DNA is made accessible to the proteins and enzymes involved in the replication process. How does the replication machinery know where on the DNA double helix to begin? It turns out that there are specific nucleotide sequences called origins of replication at which replication begins. Certain proteins bind to the origin of replication while an enzyme called helicase unwinds and opens up the DNA helix. As the DNA opens up, Y-shaped structures called replication forks are formed. Two replication forks are formed at the origin of replication, and these get extended in both directions as replication proceeds. There are multiple origins of replication on the eukaryotic chromosome, such that replication can occur simultaneously from several places in the genome.

|

During elongation, an enzyme called DNA polymerase adds DNA nucleotides to the 3' end of the template. Because DNA polymerase can only add new nucleotides at the end of a backbone, a primer sequence, which provides this starting point, is added with complementary RNA nucleotides. This primer is removed later, and the nucleotides are replaced with DNA nucleotides. One strand, which is complementary to the parental DNA strand, is synthesized continuously toward the replication fork so the polymerase can add nucleotides in this direction. This continuously synthesized strand is known as the leading strand. Because DNA polymerase can only synthesize DNA in a 5' to 3' direction, the other new strand is put together in short pieces called Okazaki fragments. The Okazaki fragments each require a primer made of RNA to start the synthesis. The strand with the Okazaki fragments is known as the lagging strand. As synthesis proceeds, an enzyme removes the RNA primer, which is then replaced with DNA nucleotides, and the gaps between fragments are sealed by an enzyme called DNA ligase.

|

Images and text are adapted under a Creative Commons 4.0 license. You can find the original source here.

|

The process of DNA replication can be summarized as follows:

|

|

|

|

|

|

More on Semi-Conservative Replication:

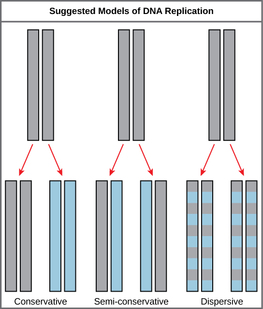

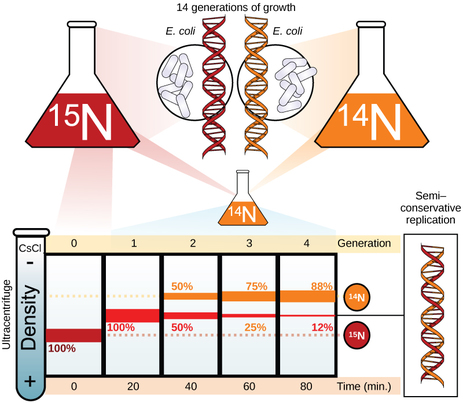

The elucidation of the structure of the double helix provided a hint as to how DNA divides and makes copies of itself. This model suggests that the two strands of the double helix separate during replication, and each strand serves as a template from which the new complementary strand is copied. What was not clear was how the replication took place. There were three models suggested: conservative, semi-conservative, and dispersive. In conservative replication, the parental DNA remains together, and the newly formed daughter strands are together. The semi-conservative method suggests that each of the two parental DNA strands act as a template for new DNA to be synthesized; after replication, each double-stranded DNA includes one parental or “old” strand and one “new” strand. In the dispersive model, both copies of DNA have double-stranded segments of parental DNA and newly synthesized DNA interspersed. Meselson and Stahl were interested in understanding how DNA replicates. They grew E. coli for several generations in a medium containing a “heavy” isotope of nitrogen (15N) that gets incorporated into nitrogenous bases, and eventually into the DNA. |

The E. coli culture was then shifted into medium containing 14N and allowed to grow for one generation. The cells were harvested and the DNA was isolated. The DNA was centrifuged at high speeds in an ultracentrifuge. Some cells were allowed to grow for one more life cycle in 14N and spun again. During the density gradient centrifugation, the DNA is loaded into a gradient (typically a salt such as cesium chloride or sucrose) and spun at high speeds of 50,000 to 60,000 rpm. Under these circumstances, the DNA will form a band according to its density in the gradient. DNA grown in 15N will band at a higher density position than that grown in 14N.

Meselson and Stahl noted that after one generation of growth in 14N after they had been shifted from 15N, the single band observed was intermediate in position in between DNA of cells grown exclusively in 15N and 14N. This suggested either a semi-conservative or dispersive mode of replication. The DNA harvested from cells grown for two generations in 14N formed two bands: one DNA band was at the intermediate position between 15N and 14N, and the other corresponded to the band of 14N DNA. These results could only be explained if DNA replicates in a semi-conservative manner. Therefore, the other two modes were ruled out.

During DNA replication, each of the two strands that make up the double helix serves as a template from which new strands are copied. The new strand will be complementary to the parental or “old” strand. When two daughter DNA copies are formed, they have the same sequence and are divided equally into the two daughter cells.

Meselson and Stahl noted that after one generation of growth in 14N after they had been shifted from 15N, the single band observed was intermediate in position in between DNA of cells grown exclusively in 15N and 14N. This suggested either a semi-conservative or dispersive mode of replication. The DNA harvested from cells grown for two generations in 14N formed two bands: one DNA band was at the intermediate position between 15N and 14N, and the other corresponded to the band of 14N DNA. These results could only be explained if DNA replicates in a semi-conservative manner. Therefore, the other two modes were ruled out.

During DNA replication, each of the two strands that make up the double helix serves as a template from which new strands are copied. The new strand will be complementary to the parental or “old” strand. When two daughter DNA copies are formed, they have the same sequence and are divided equally into the two daughter cells.

Summary:

DNA replicates by a semi-conservative method in which each of the two parental DNA strands act as a template for new DNA to be synthesized. After replication, each DNA has one parental or “old” strand, and one daughter or “new” strand.

Replication in eukaryotes starts at multiple origins of replication, while replication in prokaryotes starts from a single origin of replication. The DNA is opened with enzymes, resulting in the formation of the replication fork. Primase synthesizes an RNA primer to initiate synthesis by DNA polymerase, which can add nucleotides in only one direction. One strand is synthesized continuously in the direction of the replication fork; this is called the leading strand. The other strand is synthesized in a direction away from the replication fork, in short stretches of DNA known as Okazaki fragments. This strand is known as the lagging strand. Once replication is completed, the RNA primers are replaced by DNA nucleotides and the DNA is sealed with DNA ligase.

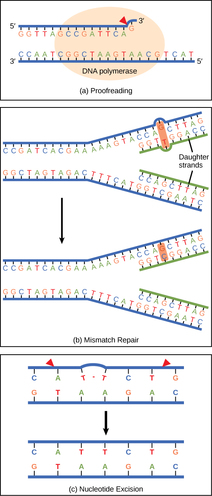

The ends of eukaryotic chromosomes pose a problem, as polymerase is unable to extend them without a primer. Telomerase, an enzyme with an inbuilt RNA template, extends the ends by copying the RNA template and extending one end of the chromosome. DNA polymerase can then extend the DNA using the primer. In this way, the ends of the chromosomes are protected. Cells have mechanisms for repairing DNA when it becomes damaged or errors are made in replication. These mechanisms include mismatch repair to replace nucleotides that are paired with a non-complementary base and nucleotide excision repair, which removes bases that are damaged such as thymine dimers.

Text and images are adapted under a Creative Commons 4.0 license. You can find the original source here.

DNA replicates by a semi-conservative method in which each of the two parental DNA strands act as a template for new DNA to be synthesized. After replication, each DNA has one parental or “old” strand, and one daughter or “new” strand.

Replication in eukaryotes starts at multiple origins of replication, while replication in prokaryotes starts from a single origin of replication. The DNA is opened with enzymes, resulting in the formation of the replication fork. Primase synthesizes an RNA primer to initiate synthesis by DNA polymerase, which can add nucleotides in only one direction. One strand is synthesized continuously in the direction of the replication fork; this is called the leading strand. The other strand is synthesized in a direction away from the replication fork, in short stretches of DNA known as Okazaki fragments. This strand is known as the lagging strand. Once replication is completed, the RNA primers are replaced by DNA nucleotides and the DNA is sealed with DNA ligase.

The ends of eukaryotic chromosomes pose a problem, as polymerase is unable to extend them without a primer. Telomerase, an enzyme with an inbuilt RNA template, extends the ends by copying the RNA template and extending one end of the chromosome. DNA polymerase can then extend the DNA using the primer. In this way, the ends of the chromosomes are protected. Cells have mechanisms for repairing DNA when it becomes damaged or errors are made in replication. These mechanisms include mismatch repair to replace nucleotides that are paired with a non-complementary base and nucleotide excision repair, which removes bases that are damaged such as thymine dimers.

Text and images are adapted under a Creative Commons 4.0 license. You can find the original source here.

DNA RepairDNA polymerase can make mistakes while adding nucleotides. It edits the DNA by proofreading every newly added base. Incorrect bases are removed and replaced by the correct base, and then polymerization continues (Figure a). Most mistakes are corrected during replication, although when this does not happen, the mismatch repair mechanism is employed. Mismatch repair enzymes recognize the wrongly incorporated base and excise it from the DNA, replacing it with the correct base (Figure b). In yet another type of repair, nucleotide excision repair, the DNA double strand is unwound and separated, the incorrect bases are removed along with a few bases on the 5' and 3' end, and these are replaced by copying the template with the help of DNA polymerase (Figure c).

Nucleotide excision repair is particularly important in correcting thymine dimers, which are primarily caused by ultraviolet light. In a thymine dimer, two thymine nucleotides adjacent to each other on one strand are covalently bonded to each other rather than their complementary bases. If the dimer is not removed and repaired it will lead to a mutation. Individuals with flaws in their nucleotide excision repair genes show extreme sensitivity to sunlight and develop skin cancers early in life. Most mistakes are corrected; if they are not, they may result in a mutation—defined as a permanent change in the DNA sequence. Mutations in repair genes may lead to serious consequences like cancer. |

Section Summary

The model for DNA replication suggests that the two strands of the double helix separate during replication, and each strand serves as a template from which the new complementary strand is copied. In conservative replication, the parental DNA is conserved, and the daughter DNA is newly synthesized. The semi-conservative method suggests that each of the two parental DNA strands acts as template for new DNA to be synthesized; after replication, each double-stranded DNA includes one parental or “old” strand and one “new” strand. The dispersive mode suggested that the two copies of the DNA would have segments of parental DNA and newly synthesized DNA.

This text is adapted under a Creative Commons 4.0 license. You can find the original source here.

You can find more information on this powerpoint.

The model for DNA replication suggests that the two strands of the double helix separate during replication, and each strand serves as a template from which the new complementary strand is copied. In conservative replication, the parental DNA is conserved, and the daughter DNA is newly synthesized. The semi-conservative method suggests that each of the two parental DNA strands acts as template for new DNA to be synthesized; after replication, each double-stranded DNA includes one parental or “old” strand and one “new” strand. The dispersive mode suggested that the two copies of the DNA would have segments of parental DNA and newly synthesized DNA.

This text is adapted under a Creative Commons 4.0 license. You can find the original source here.

You can find more information on this powerpoint.

Links to Experiment Papers

Protein Synthesis

|

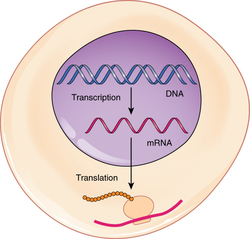

DNA provides a “blueprint” for the cell structure and physiology. This refers to the fact that DNA contains the information necessary for the cell to build one very important type of molecule: the protein. Most structural components of the cell are made up, at least in part, by proteins and virtually all the functions that a cell carries out are completed with the help of proteins. One of the most important classes of proteins is enzymes, which help speed up necessary biochemical reactions that take place inside the cell. Some of these critical biochemical reactions include building larger molecules from smaller components (such as occurs during DNA replication) and breaking down larger molecules into smaller components (such as during cellular respiration). Whatever the cellular process may be, it is almost sure to involve proteins. Just as the cell’s genome describes its full complement of DNA, a cell’s proteome is its full complement of proteins. Protein synthesis begins with genes. A gene is a functional segment of DNA that provides the genetic information necessary to build a protein. Each particular gene provides the code necessary to construct a particular protein.

|

Proteins are polymers, or chains, of many amino acid building blocks. The sequence of bases in a gene (that is, its sequence of A, T, C, G nucleotides) translates to an amino acid sequence. A triplet is a section of three DNA bases in a row that codes for a specific amino acid. Similar to the way in which the three-letter code d-o-g signals the image of a dog, the three-letter DNA base code signals the use of a particular amino acid. For example, the DNA triplet CAC (cytosine, adenine, and cytosine) specifies the amino acid valine. Therefore, a gene, which is composed of multiple triplets in a unique sequence, provides the code to build an entire protein, with multiple amino acids in the proper sequence. The mechanism by which cells turn the DNA code into a protein product is a two-step process, with an RNA molecule as the intermediate.

|

From DNA to RNA: Transcription

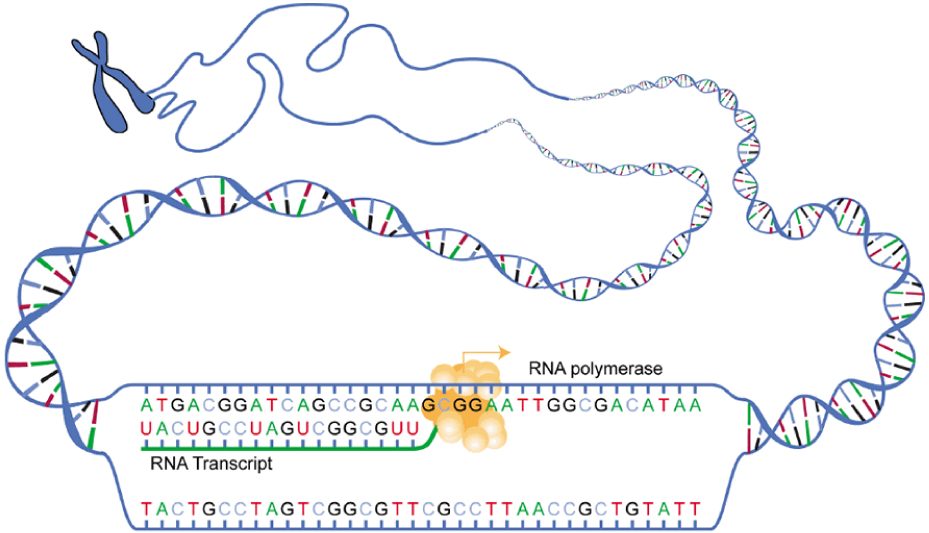

DNA is housed within the nucleus, and protein synthesis takes place in the cytoplasm, thus there must be some sort of intermediate messenger that leaves the nucleus and manages protein synthesis. This intermediate messenger is messenger RNA (mRNA), a single-stranded nucleic acid that carries a copy of the genetic code for a single gene out of the nucleus and into the cytoplasm where it is used to produce proteins. There are several different types of RNA, each having different functions in the cell. The structure of RNA is similar to DNA with a few small exceptions. For one thing, unlike DNA, most types of RNA, including mRNA, are single-stranded and contain no complementary strand. Second, instead of the base thymine, RNA contains the base uracil. This means that adenine will always pair up with uracil during the protein synthesis process. Protein synthesis begins with the process called transcription, which is the synthesis of a strand of mRNA that is complementary to the gene of interest. This process is called transcription because the mRNA is like a transcript, or copy, of the gene’s DNA code. Transcription begins somewhat like DNA replication, in that a region of DNA unwinds and the two strands separate, however, only that small portion of the DNA will be split apart. The triplets within the gene on this section of the DNA molecule are used as the template to transcribe the complementary strand of RNA. A codon is a three-base sequence of mRNA, so-called because they directly encode amino acids. Like DNA replication, there are three stages to transcription: initiation, elongation, and termination. |

Stage 1: Initiation. A region at the beginning of the gene called a promoter—a particular sequence of nucleotides—triggers the start of transcription.Stage 2: Elongation. Transcription starts when RNA polymerase unwinds the DNA segment. One strand, referred to as the coding strand, becomes the template with the genes to be coded. The polymerase then aligns the correct nucleic acid (A, C, G, or U) with its complementary base on the coding strand of DNA. RNA polymerase is an enzyme that adds new nucleotides to a growing strand of RNA. This process builds a strand of mRNA.Stage 3: Termination. When the polymerase has reached the end of the gene, one of three specific triplets (UAA, UAG, or UGA) codes a “stop” signal, which triggers the enzymes to terminate transcription and release the mRNA transcript.

|

|

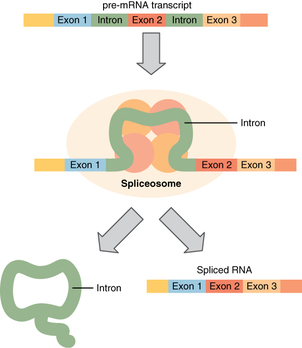

Before the mRNA molecule leaves the nucleus and proceeds to protein synthesis, it is modified in a number of ways. For this reason, it is often called a pre-mRNA at this stage. For example, your DNA, and thus complementary mRNA, contains long regions called non-coding regions that do not code for amino acids. Their function is still a mystery, but the process called splicing removes these non-coding regions from the pre-mRNA transcript (Figure). A spliceosome—a structure composed of various proteins and other molecules—attaches to the mRNA and “splices” or cuts out the non-coding regions. The removed segment of the transcript is called an intron. The remaining exons are pasted together. An exon is a segment of RNA that remains after splicing. Interestingly, some introns that are removed from mRNA are not always non-coding. When different coding regions of mRNA are spliced out, different variations of the protein will eventually result, with differences in structure and function. This process results in a much larger variety of possible proteins and protein functions. When the mRNA transcript is ready, it travels out of the nucleus and into the cytoplasm.

|

From RNA to Protein: Translation

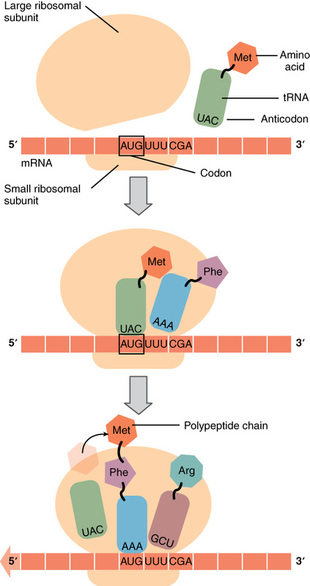

Like translating a book from one language into another, the codons on a strand of mRNA must be translated into the amino acid alphabet of proteins. Translation is the process of synthesizing a chain of amino acids called a polypeptide. Translation requires two major aids: first, a “translator,” the molecule that will conduct the translation, and second, a substrate on which the mRNA strand is translated into a new protein, like the translator’s “desk.” Both of these requirements are fulfilled by other types of RNA. The substrate on which translation takes place is the ribosome. Ribosomes exist in the cytoplasm as two distinct components, a small and a large subunit. When an mRNA molecule is ready to be translated, the two subunits come together and attach to the mRNA. The ribosome provides a substrate for translation, bringing together and aligning the mRNA molecule with the molecular “translators” that must decipher its code.

Like translating a book from one language into another, the codons on a strand of mRNA must be translated into the amino acid alphabet of proteins. Translation is the process of synthesizing a chain of amino acids called a polypeptide. Translation requires two major aids: first, a “translator,” the molecule that will conduct the translation, and second, a substrate on which the mRNA strand is translated into a new protein, like the translator’s “desk.” Both of these requirements are fulfilled by other types of RNA. The substrate on which translation takes place is the ribosome. Ribosomes exist in the cytoplasm as two distinct components, a small and a large subunit. When an mRNA molecule is ready to be translated, the two subunits come together and attach to the mRNA. The ribosome provides a substrate for translation, bringing together and aligning the mRNA molecule with the molecular “translators” that must decipher its code.

|

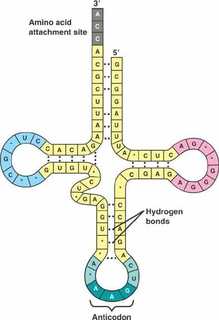

The other major requirement for protein synthesis is the translator molecules that physically “read” the mRNA codons. Transfer RNA (tRNA) is a type of RNA that ferries the appropriate corresponding amino acids to the ribosome, and attaches each new amino acid to the last, building the polypeptide chain one-by-one. Thus tRNA transfers specific amino acids from the cytoplasm to a growing polypeptide. The tRNA molecules must be able to recognize the codons on mRNA and match them with the correct amino acid. The tRNA is modified for this function. On one end of its structure is a binding site for a specific amino acid. On the other end is a base sequence that matches the codon specifying its particular amino acid. This sequence of three bases on the tRNA molecule is called an anticodon. For example, a tRNA responsible for shuttling the amino acid glycine contains a binding site for glycine on one end. On the other end it contains an anticodon that complements the glycine codon (GGA is a codon for glycine, and so the tRNAs anticodon would read CCU). Equipped with its particular cargo and matching anticodon, a tRNA molecule can read its recognized mRNA codon and bring the corresponding amino acid to the growing chain .

|

|

Much like the processes of DNA replication and transcription, translation consists of three main stages: initiation, elongation, and termination.

|

CHAPTER REVIEW:

DNA stores the information necessary for instructing the cell to perform all of its functions. Cells use the genetic code stored within DNA to build proteins, which ultimately determine the structure and function of the cell. This genetic code lies in the particular sequence of nucleotides that make up each gene along the DNA molecule. To “read” this code, the cell must perform two sequential steps. In the first step, transcription, the DNA code is converted into a RNA code. A molecule of messenger RNA that is complementary to a specific gene is synthesized in a process similar to DNA replication. The molecule of mRNA provides the code to synthesize a protein. In the process of translation, the mRNA attaches to a ribosome. Next, tRNA molecules shuttle the appropriate amino acids to the ribosome, one-by-one, coded by sequential triplet codons on the mRNA, until the protein is fully synthesized. When completed, the mRNA detaches from the ribosome, and the protein is released.

Text and images are adapted under a Creative Commons 4.0 license. You can find the original source here.

You can also find more information on the powerpoint.

DNA stores the information necessary for instructing the cell to perform all of its functions. Cells use the genetic code stored within DNA to build proteins, which ultimately determine the structure and function of the cell. This genetic code lies in the particular sequence of nucleotides that make up each gene along the DNA molecule. To “read” this code, the cell must perform two sequential steps. In the first step, transcription, the DNA code is converted into a RNA code. A molecule of messenger RNA that is complementary to a specific gene is synthesized in a process similar to DNA replication. The molecule of mRNA provides the code to synthesize a protein. In the process of translation, the mRNA attaches to a ribosome. Next, tRNA molecules shuttle the appropriate amino acids to the ribosome, one-by-one, coded by sequential triplet codons on the mRNA, until the protein is fully synthesized. When completed, the mRNA detaches from the ribosome, and the protein is released.

Text and images are adapted under a Creative Commons 4.0 license. You can find the original source here.

You can also find more information on the powerpoint.

|

|

|

The Reading Frame

The reading frame is the frame of three bases in which the mRNA is read or translated. Every sequence can be read in three reading frames, each of which will produce a different amino acid sequence. For example, in the sequence GCAUGGGGGUCUAG, the reading frame can begin with either the first G, the first C, or the first A. As stated above, translation starts with the start codon which consists of the three bases AUG. Each subsequent codon is translated until an in-frame stop codon is reached. In the example above, the polypeptide sequence would be: methionine – glycine – valine – stop.

To find the open reading frame on the DNA strand you have to find the first ATG triplet after the promoter. Read this discussion of why ATG is the start of the ORF.

The reading frame is the frame of three bases in which the mRNA is read or translated. Every sequence can be read in three reading frames, each of which will produce a different amino acid sequence. For example, in the sequence GCAUGGGGGUCUAG, the reading frame can begin with either the first G, the first C, or the first A. As stated above, translation starts with the start codon which consists of the three bases AUG. Each subsequent codon is translated until an in-frame stop codon is reached. In the example above, the polypeptide sequence would be: methionine – glycine – valine – stop.

To find the open reading frame on the DNA strand you have to find the first ATG triplet after the promoter. Read this discussion of why ATG is the start of the ORF.

|

MUTATIONS:

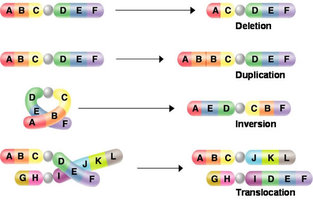

A mutation is a change in the nucleotide sequence of an organisms DNA. A common example would be binding a cytosine in place of a thymine. These mistakes can be made during DNA replication, transcription, or translation. Mutations may be of two types: induced or spontaneous. Induced mutations are those that result from an exposure to chemicals, UV rays, x-rays, or some other environmental agent. Spontaneous mutations occur without any exposure to any environmental agent; they are a result of natural reactions taking place within the body. |

|

Mutations may have a wide range of effects. Some mutations are not expressed; these are known as silent mutations. These silent mutations have no affect on the resulting protein. The most common silent mutations are point mutations are those mutations that affect a single base pair. The most common nucleotide mutations are substitutions, in which one base is replaced by another. Mutations can also be the result of the addition of a base, known as an insertion, or the removal of a base, also known as deletion. Sometimes a piece of DNA from one chromosome may get translocated to another chromosome or to another region of the same chromosome; this is also known as translocation.

|

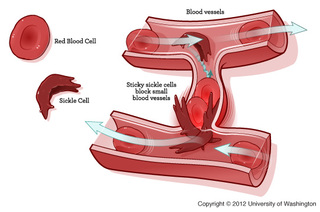

If the mutation results the code for a different amino acid then the resulting protein will be changed. This change could be beneficial or detrimental, or it could result in no change in the function of the protein. The mutation that causes sickle cell anemia is caused by one amino acid being exchanged for another. The result of this amino acid switch is a change the in the shape of the red blood cell that contains the haemoglobin protein. The resulting red blood cells are sickle shaped. This thin and pointy shape makes them prone to getting stuck in blood vessels, causing clots. These sickle shaped red blood cells are not able to carry as much oxygen as their normal counterparts. However, the gene for sickle cell anemia is not all bad, people with the gene are protected from malaria.

Mutations in repair genes have been known to cause cancer. Many mutated repair genes have been implicated in certain forms of pancreatic cancer, colon cancer, and colorectal cancer. Mutations can affect either somatic cells or germ cells. If many mutations accumulate in a somatic cell, they may lead to problems such as the uncontrolled cell division observed in cancer. If a mutation takes place in germ cells, the mutation will be passed on to the next generation, as in the case of hemophilia.

This text is adapted under a Creative Commons 4.0 license. You can find the original source here.

This text is adapted under a Creative Commons 4.0 license. You can find the original source here.

|

|

|

Enzymes

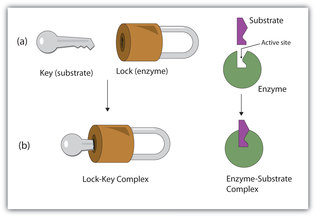

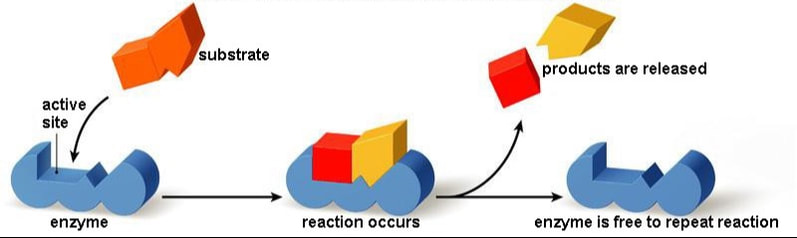

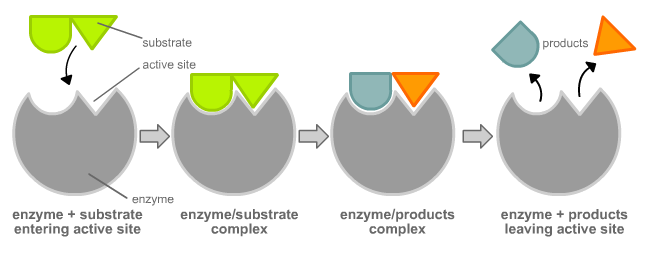

A substance that helps a chemical reaction to occur is a catalyst, and the special molecules that catalyze biochemical reactions are called enzymes. Almost all enzymes are proteins, made up of chains of amino acids, and they perform the critical task of lowering the amount of energy needed for the chemical reaction to take place inside the cell. Enzymes do this by binding to the reactant molecules, and holding them in such a way as to make the chemical bond-breaking and bond-forming processes take place more readily.

|

The chemical reactants to which an enzyme binds are the enzyme’s substrates. There may be one or more substrates, depending on the particular chemical reaction. In some reactions, a single-reactant substrate is broken down into multiple products. In others, two substrates may come together to create one larger molecule. Two reactants might also enter a reaction, both become modified, and leave the reaction as two products. The location within the enzyme where the substrate binds is called the enzyme’s active site. The active site is where the “action” happens, so to speak. Since enzymes are proteins, there is a unique combination of amino acids in the enzyme's active site. The unique combination of amino acid, their positions, sequences, structures, and properties, creates a very specific chemical environment within the active site. This specific environment is suited to bind to a specific chemical substrate (or substrates). Due to this jigsaw puzzle-like match between an enzyme and its substrates, enzymes are known for their specificity. The “best fit” results from the shape and the attraction to the substrate of the amino acids in the active site . There is a specifically matched enzyme for each substrate and, thus, for each chemical reaction. Each enzyme will work with only one type of substrate. This is called the "lock and key" hypothesis.

|

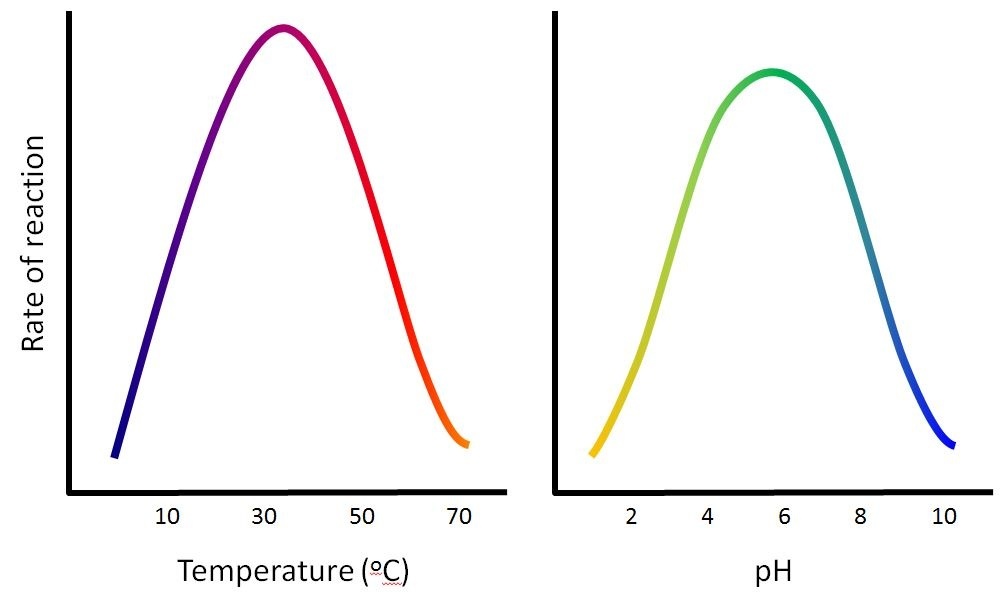

The fact that active sites are so perfectly suited to provide specific environmental conditions also means that they are subject to influences by the local environment. This means that changing the local pH or temperature can change the nature of the active site, changing how it is attracted to the substrate. Increasing or decreasing the temperature outside of an optimal range can affect chemical bonds within the active site in such a way that they are less well suited to bind substrates. High temperatures will eventually cause enzymes, like other biological molecules, to denature, a process that changes the natural properties of a substance. Likewise, the pH of the local environment can also affect enzyme function. Active site amino acid residues have their own acidic or basic properties that are optimal for catalysis. These residues are sensitive to changes in pH that can impair the way substrate molecules bind. Enzymes are suited to function best within a certain pH range, and, as with temperature, extreme pH values (acidic or basic) of the environment can cause enzymes to denature.

Section Summary

Enzymes are chemical catalysts that accelerate chemical reactions at physiological temperatures by lowering their activation energy. Enzymes are usually proteins consisting of one or more polypeptide chains. Enzymes have an active site that provides a unique chemical environment, made up of certain amino acids. This unique environment is perfectly suited to convert particular chemical reactants for that enzyme, called substrates, into unstable intermediates called transition states. Enzymes and substrates are thought to bind with lock and key fit, which means that enzyme's active site matches with a specific substrate. Enzymes bind to substrates and catalyze reactions in four different ways: bringing substrates together in an optimal orientation, compromising the bond structures of substrates so that bonds can be more easily broken, providing optimal environmental conditions for a reaction to occur, or participating directly in their chemical reaction by forming transient covalent bonds with the substrates.

This text is adapted under a Creative Commons 4.0 license. You can find the original source here. You can also find more information on the powerpoint.

Enzymes are chemical catalysts that accelerate chemical reactions at physiological temperatures by lowering their activation energy. Enzymes are usually proteins consisting of one or more polypeptide chains. Enzymes have an active site that provides a unique chemical environment, made up of certain amino acids. This unique environment is perfectly suited to convert particular chemical reactants for that enzyme, called substrates, into unstable intermediates called transition states. Enzymes and substrates are thought to bind with lock and key fit, which means that enzyme's active site matches with a specific substrate. Enzymes bind to substrates and catalyze reactions in four different ways: bringing substrates together in an optimal orientation, compromising the bond structures of substrates so that bonds can be more easily broken, providing optimal environmental conditions for a reaction to occur, or participating directly in their chemical reaction by forming transient covalent bonds with the substrates.

This text is adapted under a Creative Commons 4.0 license. You can find the original source here. You can also find more information on the powerpoint.

Environmental factors influence enzyme activity

The fact that active sites are so perfectly suited to provide specific environmental conditions also means that they are subject to influences by the local environment. The environmental conditions can include temperature, pH, salinity and presence of heavy metals. It is true that increasing the environmental temperature generally increases reaction rates, enzyme-catalyzed or otherwise. However, increasing or decreasing the temperature outside of an optimal range can affect chemical bonds within the active site in such a way that they are less well suited to bind substrates. High temperatures will eventually cause enzymes, like other biological molecules, to denature, a process that changes the natural properties of a substance. Likewise, the pH of the local environment can also affect enzyme function. Active site amino acids have their own acidic or basic properties that are optimal for catalysis. These amino acids are sensitive to changes in pH that can impair the way substrate molecules bind. Enzymes are suited to function best within a certain pH range, and, as with temperature, extreme pH values (acidic or basic) of the environment can cause enzymes to denature an the rates of the reaction decrease.

The fact that active sites are so perfectly suited to provide specific environmental conditions also means that they are subject to influences by the local environment. The environmental conditions can include temperature, pH, salinity and presence of heavy metals. It is true that increasing the environmental temperature generally increases reaction rates, enzyme-catalyzed or otherwise. However, increasing or decreasing the temperature outside of an optimal range can affect chemical bonds within the active site in such a way that they are less well suited to bind substrates. High temperatures will eventually cause enzymes, like other biological molecules, to denature, a process that changes the natural properties of a substance. Likewise, the pH of the local environment can also affect enzyme function. Active site amino acids have their own acidic or basic properties that are optimal for catalysis. These amino acids are sensitive to changes in pH that can impair the way substrate molecules bind. Enzymes are suited to function best within a certain pH range, and, as with temperature, extreme pH values (acidic or basic) of the environment can cause enzymes to denature an the rates of the reaction decrease.

|

The temperatures and pHs that are most effective will change with each enzyme. Enzymes in the human body are most affective at a temperature of 37 degrees celsius as this is the normal body temperature. If you have a fever your body temperature increases making enzymes less effective. This is your body's natural defense to invaders. The idea is that the invaders will die as their enzymes will no longer work. However, if your fever increases too much your enzymes will also be affected and you may also die.

The enzymes in your body are also most functional at specific pH levels. In the stomach there is a high acidity due to the hydrochloric acid used to break down food and kill bacteria. As a result, only protease (the enzymes that break down proteins) are functional in the stomach as they have an optimum pH of about 2. Amylase, which is functional in the mouth and small intestine works at a much higher pH, one much closer to 6. Text and images are adapted under a Creative Commons 4.0 license. You can find the original source here. |

|

Proudly powered by Weebly